METEORISATIONS Reading Amílcar Cabral’s agronomy of liberation

This article1 reads Amílcar Cabral’s much under-studied early soil science as a body of work not dissociable from his project of liberation struggle against Portuguese colonialism in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. Drawing on research situated within an artistic practice, the article explores the definitions of soil and erosion that Cabral developed as an agronomist, as well as his reports on colonial land exploitation and analysis of the trade economy, to unearth his double agency as a state soil scientist and as a ‘seeder’ of African liberation. Cabral understood agronomy not merely as a discipline combining geology, soil science, agriculture, biology and economics but as a means to gain materialist and situated knowledge about peoples’ lived conditions under colonialism. The scientific data he generated during his work as an agronomist were critical to his theoretical arguments in which he denounced the injustices perpetrated on colonised land, and it later informed his warfare strategies. Cabral used his role as an agronomist for the Portuguese colonial government subversively to further anti-colonial struggle. I argue that the results of Cabral’s agronomic work – his care for the soil and attention to its processes and transformations – not only informed the organization of the liberation struggle, but were crucial to the process of decolonisation, understood as a project of reclamation and national reconstruction in the postcolony.

***

Our people are our mountains.2

Amílcar Cabral

‘Mining’ historical strata to almost half a century ago, we find Amílcar Cabral at the University of London on 27 October 1971 describing the state of the armed struggle he had led since 1963 in the country that was then known as Portuguese Guinea. After eight years of anti-colonial war, two thirds of the small West African country had been freed from Portuguese occupation. Within these ‘Liberated Zones’ that spread across areas of tropical forest the PAIGC (African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde) established schools, hospitals, courts and people’s communal shops. During these years, Cabral moved between the party headquarters in Conakry in neighbouring Guinea, the jungle of the guerrilla within Guinea-Bissau and the international geo-political realm where he was advocating for and attempting to develop a new society3. At the lecture in London in 1971 he described the conditions of the armed struggle in Guinea-Bissau:

We are in a flat part of Africa. […] The manuals of guerrilla warfare generally state that a country has to be of a certain size to be able to create what is called a base and, further, that mountains are the best place to develop guerrilla warfare. […] Obviously we don’t have those conditions in Guinea, but this did not stop us beginning our armed liberation struggle. […] As for the mountains, we decided that our people had to take their place, since it would be impossible to develop our struggle otherwise. So our people are our mountains.4

His audience was made up of young British students, leftist activists, migrants and other supporters of the London-based Committee for Freedom in Mozambique, Angola and Guinea (CFMAG), who had gathered to hear a first-hand account of an on-going anti-colonial struggle in Guinea-Bissau.5 Cabral’s metonymy – mountains = people – refers in part to the morphological flatness characterising the surface of this specific West African terrain as well as to the lack of a hierarchical structure in the anti-colonial movement.6 However, it also reveals the intimate relation that Cabral maintained with the material matter of mountains, composed of soil and bedrock. While for Che Guevara’s guerrilla in Cuba the mountains were a resource that secured locations where they could establish their bases and consolidate their power7, Cabral ‘flattens’ that strategy to adapt it to his specific geo-political circumstances. In Guinea the PAIGC had succeeded in uniting the people within a horizontally organised anti-colonial movement that prioritised education and humility as weapons of militant struggle; where peasant work and intellectual labour were of equal value instead of being submitted to a hierarchical valorisation. The mountains were the people made potent, the multitude8. Furthermore, and less metaphorically, this pattern – looking at masses of militants and seeing the potential strategic force of mountains—reflects his understanding of the world in ‘ecosophical’ terms, i.e., a holistic understanding of ecology.9 This resonates with the less known and often neglected dimension of Cabral’s practice as an agronomist and how his research on soil and erosion informed his political formation.

This article makes a reading of Cabral’s agronomical texts, which were published in the book Estudos Agrários de Amílcar Cabral (Agrarian Studies of Amílcar Cabral) 1948 to 1960, alongside his more widely translated and published speeches and political writings10. The context for this reading is an on-going engagement with Cabral’s thought that has included filmmaking, artistic activism through the digitalisation of militant cinema from Guinea Bissau, and working with Guinean filmmakers such as Sana N’Hada and Flora Gomes, among others11. I started writing notes on Cabral’s agronomical writing in 2009 when I first encountered his book Estudos Agrários de Amílcar Cabral in a second-hand bookshop in Lisbon, an event that informed many of my films and installations, especially the project Luta ca caba inda (2011-ongoing).

Voluntary work by Guinean students and camera exercise in Cuba, Dervis Espinosa, Cuba, INCA, 1967

Voluntary work by Guinean students and camera exercise in Cuba, Dervis Espinosa, Cuba, INCA, 1967

In Cabral’s thought the geological is not separated from human history, the soil is not an inert and static ‘ground’ subjected to human agency, but rather has a dynamic relation to human social structures, evident in its different responses to forms of colonial extractivism. An example of this interrelation was the devastating drought in Cape Verde in 1941, which took the life of 20,000 people, and was witnessed by Cabral at the age of 17. According to his daughter, Iva Cabral, this experience influenced his decision to become an agronomist12. While in the twentieth century, geology was for the most part understood, at least in the West, as the static backdrop to human action, recent scholarly work by thinkers such as Dipesh Chakrabarty has recognised that to fully apprehend the unfolding environmental crisis sometimes referred to as the cause for defining a new Earth epoch – the Anthropocene or Capitalocene13, it is necessary to question and put in dialogue the concepts of natural history and human history14. Cabral was prescient when he said ‘we can affirm, without fear of contradiction […] that, to defend the Earth is the most efficient process to defend Humankind.’15 As this article will explore, by drawing on earlier soil scientists who recognised the catastrophic environmental consequences of capitalist colonialism, Cabral was ahead of his time.

Cabral’s understanding of soil and erosion are not dissociable from his project of liberation struggle. His reports on colonial land exploitation and the trade economy, along with his research on soil and erosion, reveal his double agency as a state soil scientist and as a ‘sower’ of African liberation. Between 1949 and 1950, while working as an agronomist for the colonial regime and simultaneously participating in the formation of a clandestine anti-colonial movement, Cabral wrote ‘Em Defesa da Terra I–IV’ (‘In Defence of the Earth I–IV’). This article developed a militant semantics for soil reclamation that was part of a project of liberation. In his 1971 speech in London Cabral stated: ‘In 1960, I was the only agronomist in my country – what a privilege! – but now there are twelve agronomists in my country, all trained during the struggle.’ Cabral understood agronomy not merely as a discipline combining geology, soil science, agriculture, biology and economics but as a means to gain materialist knowledge about peoples’ lived conditions under colonialism.

Cabral’s life has been extensively explored in notable biographies, ranging from that of Patrick Chabal to more recent works by António Tomás and Julião Soares Sousa16. As a young student of agronomy, Cabral carried out research in Cuba, a flat and dry area in southern Portugal that was economically disadvantaged. This gave him early insights into the importance of connecting a militant knowledge with theory17. Portuguese historian and theorist José Neves recently proposed that Cabral’s interest in pedology – the formation, chemistry, morphology, and classification of the soil –– was informed by an ‘ecological concern’ not limited to an attention to ‘land and its fauna and flora but to the men and their social relations’18. The scientific data Cabral gathered during his work as an agronomist first became instrumental in the theoretical and political argument denouncing the injustice perpetrated on land inscribed by colonial rule, and would later inform his military strategy. Care for the soil was crucial for Cabral as part of the work of reclamation (of soil and more) necessary in the project of national reconstruction in the postcolony19. The operation of reading the ‘people’ as ‘mountains’ in the context of colonial extraction, oppression and exploitation evidences a visionary understanding of the capitalocenic condition of the surface of the earth. In his agronomic writings Cabral refers to the edaphology – from the Greek ἔδαφος, edaphos, or “ground”, and λογία - logia – as the science that is concerned with the influence of soils on living things. The logic of this concept – from the ground up – and the reciprocity it conveys lays the groundwork for the principles from where he articulated the struggle.

LITHOS-ATMOS CONFLICT

The soil is a natural, independent and historical body.

Vasily Dokuchaev

Cabral’s experience as a student of agronomy and his research in Southern Portugal’s Cuba region gave him an indication of the importance of understanding the role of soil and integrating it in a conception of the world. In his 1949 bachelor degree dissertation, ‘Erosion of Agricultural Soils, an Investigation of the Alentejo Region of Cuba,’ he described this economically poor area whose land was rapidly desertifying during the fascist dictatorship of Antonio de Oliveira Salazar between 1933-74. This fieldwork allowed him to develop his distinct interest in soil and the phenomenon of its erosion, drawing particularly from work in the field of soil science that had emerged since the mid-nineteenth century such as Justus von Liebig, Ferdinand von Richthofen and especially, Vasily Dokuchaev. In his agronomic studies of the Alentejo region he utilises Liebig’s chemical definition of soil as a laboratory in which to verify the most varied chemical reactions, Richthofen’s geological perspective of soil as a pathological condition of the rock, and Dokuchaev’s definition of soil as a natural, independent and historical body. This emerging science had an impact on materialist political thought, especially on Marx, and later contributed to Cabral’s anti-colonialist arguments that condemned the agricultural and extractive practices of colonial powers.

Soil map by Amílcar Cabral for the study ‘O Problema da Erosão do Solo. Contribuição para o seu Estudo na Região de Cuba (Alentejo)’, 1951, source Estudos Agrários de Amílcar Cabral, Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical, Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisa Lisboa and Bissau, 1988, p 174Cabral stressed the importance of not defining soil through its ‘static-morphological’ aspect but through its variables and its relational and dynamic potential: ‘The being from which the soil derives is the rock. Through natural or artificial action the rock is fragmented, disintegrated and forms what is called in edaphology “original matter”. The “meteorisation of the rock”.’ He refers to this as a relative ‘negation’ of the rock, where natural agents destroy its structure and negate it, creating ‘original matter’–– the matter resulting from the destruction of the rock before it has become soil. Subsequently, a second negation in the meteorisation process corresponds to the development of the ‘body-soil’ – which he identifies as independent, natural and historical. ‘This balance is sustained through the contradiction generated by successive transformations. Oxidations, reductions, carbonisations, dissolutions, hydrolyses, volume variations, compost translocations, micro-organic activities.’ Cabral elaborates on a coevality of the ‘lithos’ (rock) and ‘atmos’ (climatic) forces, a zone of destruction and transformation between independent elements and from which life is possible. From this, soil can be understood as ‘the crust of meteorisation’.

Soil map by Amílcar Cabral for the study ‘O Problema da Erosão do Solo. Contribuição para o seu Estudo na Região de Cuba (Alentejo)’, 1951, source Estudos Agrários de Amílcar Cabral, Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical, Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisa Lisboa and Bissau, 1988, p 174Cabral stressed the importance of not defining soil through its ‘static-morphological’ aspect but through its variables and its relational and dynamic potential: ‘The being from which the soil derives is the rock. Through natural or artificial action the rock is fragmented, disintegrated and forms what is called in edaphology “original matter”. The “meteorisation of the rock”.’ He refers to this as a relative ‘negation’ of the rock, where natural agents destroy its structure and negate it, creating ‘original matter’–– the matter resulting from the destruction of the rock before it has become soil. Subsequently, a second negation in the meteorisation process corresponds to the development of the ‘body-soil’ – which he identifies as independent, natural and historical. ‘This balance is sustained through the contradiction generated by successive transformations. Oxidations, reductions, carbonisations, dissolutions, hydrolyses, volume variations, compost translocations, micro-organic activities.’ Cabral elaborates on a coevality of the ‘lithos’ (rock) and ‘atmos’ (climatic) forces, a zone of destruction and transformation between independent elements and from which life is possible. From this, soil can be understood as ‘the crust of meteorisation’.

The definition of ‘meteorisation of the rock’, as a negation of one in order to give rise to another, informs a dialectical and materialistic search to re-define soil as a zone of conflict. Cabral carefully notes the utility of embracing conflict and contradiction (negation and destruction):

‘The conflict between lithos and atmos is due to the antagonisms between rock and climate – if we admitted the existence of intention in natural phenomena, we could argue that this “opposition” demands that the rock transforms itself in order to subsist. Neither the rock disappears completely, nor the climatic phenomena cease to operate – rather the rock gets integrated into a new form of negation-existence.’

Experimental Farm of Pessubé, Guinea Bissau, photographer unknown, undated, source CasaComum.org

Experimental Farm of Pessubé, Guinea Bissau, photographer unknown, undated, source CasaComum.org

This observation – intention in natural phenomena – can be read as an urge to allow for a kind of rock agency: the rock/soil as carrier of a prose, a narrative, the substrate where everything is inscribed20. This echoes what Chakrabarty describes as a ‘geophysical force’; this, he writes, ‘is what in part we are in our collective existence – [it] is neither subject nor an object. A force is the capacity to move things. It is pure, nonontological agency.’ Cabral reads the soil, the historical body, listening to its processes and later parsing a parallel with what was occurring within the Guinean people (‘the mountains’). As stated earlier, meteorisation – the conflict between lithos and atmos – involves two elements in a relation of contradiction. This geomantic drive, a channel to read the earth –– its future inscribed in its pasts –– gives access to an epistemology of the edaphosphere (the layer of soil that supports and effects multiple interconnected forms of life) that speaks of how the soil’s discrete elements contain valuable information for the de-colonial struggle. The metonymy is that people are a part of the soil, the soil is a part of the people. Cabral stating that the people are our mountains means that the people themselves are the terrain of the struggle in contrast to Guevara’s notion of geological mountains as an instrument offering refuge to militants. The approach Cabral takes is reminiscent of the historical materialist operation Karl Marx carries out in Capital, although expanding the analysis in order to include environmental phenomena as having agency21. He summarises the definition of soil with an equation, where soil is the sum of all the properties and meteorisations in a given period of time:

t

S= { f [c(t), o(t), v(t), h(t), r(t), p(t), t, …] dt

to

‘S—properties of soil; c—climate; o—organism; r—topography; p—original matter; t—time; s—soil; v— vegetation; h—human being [dt—development in time]’

This could be expanded further into the equation: the palimpsest of the soil + inscribed over time = history.

Experimental Farm of Pessubé, Guinea Bissau, photographer unknown, undated, source CasaComum.org

Experimental Farm of Pessubé, Guinea Bissau, photographer unknown, undated, source CasaComum.org

COLONIAL EROSION

Planting is the root of ownership and the waging of war22.

Vilém Flusser

After defining soil as a place of conflict, Cabral continued with concepts of erosion. Operating under the constraints of dictatorial Portugal, his activity as an agronomist was subversive — he advanced the liberation struggle from inside, using colonial resources to inform and strengthen the liberation movement. Cabral defines erosion, the displacement of soil from the surface of the earth by natural agents such as water and wind, as a natural phenomenon that is ‘realised slowly and gradually within the heart of balance soil-life-climate’. This natural balance can be threatened by the erosion caused by human intervention. Cabral’s works on documenting the loss of balance produced by colonial intervention should be read in the context of an oppressive system utilising censorship to enforce its power23.

The critical situation of Portuguese agriculture led him to study Alentejo’s edaphosphere24, with a specific focus on the main cause of its crisis — soil erosion. He examined the colonial mainland and interpreted the condition of its soil depletion as the result of Portugal’s exploitation of land elsewhere. ‘[T]he Alentejo panorama clearly reflects the influences of the historical process in the province. […] the maritime voyages of discovery resulted in the creation of an empire which led to the neglect of domestic agriculture as the riches from India were more attractive than the uncertainty of labouring their own land.’25

E= f (c,r,v,s,h)

E—erosion, f—factors, c—climate, r—topography, v—vegetation, s—soil, h—human

Soil is the inscribed body and erosion the scar left by historical violence.

Although in his official agronomic work, Cabral’s references to Justus von Liebig solely address issues concerning the chemistry of the rock (‘soil is a laboratory to observe chemical reactions’), it is likely that Cabral would have also read Liebig’s political positions on the geo-economical discussion on soil. Liebig was important for Marx in his analysis of soil and historical materialism as John Bellamy Foster points out: ‘when he wrote Capital [in the 1860’s], Marx had become convinced of the contradictory and unsustainable nature of capitalist agriculture’, mainly due to historical developments such as the depletion of soil fertility through the loss of soil nutrients and the shift in Liebig’s own work towards an ecological critique of capitalist agriculture. Marx underlined the ecological impacts of these developments: ‘All progress in capitalist agriculture26 is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the worker, but of robbing the soil; all progress in increasing the fertility of the soil for a given time is a progress toward ruining the more long-lasting sources of that fertility.’

Experimental Farm of Pessubé, Guinea Bissau, photographer unknown, undated, source CasaComum.org

Experimental Farm of Pessubé, Guinea Bissau, photographer unknown, undated, source CasaComum.org

Although Cabral had read Liebig, Dokuchaev, Marx and others, when he was later asked about his ideological sources at his University of London’s lecture, he responded: ‘Moving from the realities of one’s own country towards the creation of an ideology for one’s struggle doesn’t imply that one has pretensions to be a Marx or a Lenin or any other great ideologist, but is simply a necessary part of the struggle.’ It was politically expedient for the leaders of the African liberation movements to stress that their political organisations were grassroots, and that their theories were based on the experiences of their struggles rather than imported political theory. However, they were of course influenced by European and pan-African thinkers. Cabral does not emulate the words of Liebig or even the theories of Marx, but operates similar gestures of cognisance assembled with situated knowledge, ie, from a non-Eurocentric perspective27.

Instead of studying the colonised African soil (his primary concern), Cabral began with the specificities of the oppressor’s terrain: Portugal’s own systemic crisis and its inherent propensity for violent solutions. This work on Portuguese soil erosion qualified Cabral to be employed as an agronomist by the colonial state in the ‘overseas provinces’28. In 1952, Cabral was employed by the Overseas Ministry to engage in a one-year study on the farming practices in Portuguese Guinea, the land of his birth. Here, Cabral established what he called an experimental laboratory at Pessubé Farm and, in 1953, undertook an agricultural census: a process of data collection that provided him with a direct connection to the population and access to topographical data throughout the country. This census, which comprised a study of the state of agriculture in Portugal’s colonies, has been required of the Portuguese Government by the United Nations’ Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO)29. As Guinean agronomist Carlos Schwarz suggests, when Cabral started work as an agronomist in Guinea he was convinced that the independence process would unfold peacefully, in the form in which it proceeded in many of the African countries that had been colonised by other European powers. Accordingly, he started work on a new concept of agriculture intended to replace the existing colonial model.

Cabral published a series of agronomic articles including ‘In Defence of the Earth I-IV’ and ‘Acerca da Utilização da Terra na África Negra’ (‘On the Use of the Earth in Black Africa’) in 1954. In the first, Cabral sought out historical global economic cases, addressing soil reclamation: ‘Examples of propaganda are insufficient to solve a problem whose roots plunge into the very economic structure of societies.’30 In the second, he centred on the principal human components of agriculture and its economies: ‘The fundamental source and determining aspect are the human-social-beings themselves, whose actions are dependent upon the economic structure sustained by agricultural activities.’31 He goes on to address the violence of State imposed soil politics and their contradictions:

‘The cultural system redolent of Black Africa is an itinerant system. […] a portion of jungle or savannah is chosen for cultivation; the natural vegetation is thinned and then burned; the earth is exploited for a short period and then abandoned; the forest or the savannah then reclaims the land’. […] The itinerant system (nomadic agriculture) demands a high level of settlement instability. The people don’t attach themselves to the land. This attachment would seem to be an essential condition of the process of development.’

Cabral explained how the itinerant agricultural system is an endemic solution to the problems imposed by the Black African environment and became acute in his criticism of colonial agricultural measures:

‘In short, colonialism has introduced a new system of production into Africa, which translates as an économie de traite (trade economy)32. However it maintains the nomadic system of cultivating the land. Attempts are made to apply this to the itinerant system without taking into account the specificities of the mesologic [ecological] conditions. These differ from European agricultural practices, but Europe is convinced of the “superiority” of its own practices.’33

Cabral denounced the exploitative effects of the extractionist trade economy. He built on Liebig’s description of the situation created as soon as the empirical agriculture of the trader becomes a spoliation system, and the conditions of reproduction of the soil are undermined – ‘every system of farming based on the spoliation of the land leads to poverty.’34 Cabral acknowledged that itinerant agriculture does not allow for certain cultural and infrastructural developments because of its rootlessness. However, he argued that:

‘The evolution of new African cultural technologies in the sense of better serving the progress of black African people cannot ignore the fact that they have a profound knowledge about the environment and its possibilities. […] The fact that this vital need is neglected has already led to several catastrophes. At the heart of these can generally be found a complex mesh of components introduced into the life of black Africa by a new entity — colonialism.’

As Bellamy Foster points out, Marx was initially interested in Liebig’s pioneering developments in artificial fertiliser, although he later became sceptical about their long term value: ‘Fertility is not so natural a quality as might be thought; it is closely bound up with the social relations of the time.’ This emphasis on historical changes in soil fertility in the direction of agricultural improvement becomes a constant in Marx’s later thinking, though it is eventually coupled with an understanding of how capitalist agriculture could undermine the conditions of soil fertility, resulting in soil degradation rather than improvement. ‘It is in his later work on political economy that Marx provided his systematic treatment of such issues as soil fertility, organic recycling, and sustainability in response to the investigations of the great German chemist Justus von Liebig –– and in which we find the larger conceptual framework, emphasising the ‘metabolic rift’ between human production and its natural condition.’ Cabral was efficiently compiling a body of situated knowledge – the specificities of the conflict between Africa and Portugal, a colonial power – informed by Marx and Liebig about the global dimension of the agricultural crisis nearly a century earlier.

Flora Gomes during the shooting for the film, José Bolama Cobumba, Josefina Crato, Flora Gomes, Sana na N’Hada, Guinea Bissau 6 Years After (unfinished film), INCA 1979–1980

Flora Gomes during the shooting for the film, José Bolama Cobumba, Josefina Crato, Flora Gomes, Sana na N’Hada, Guinea Bissau 6 Years After (unfinished film), INCA 1979–1980

Fascist colonial Portugal was a very particular corporate Catholic paternalistic regime, characterised by a dictatorship sustained by censorship and the rhetorical construction of fantasies about a power and reach of its empire. In reality, the country was deeply backwards. The illiteracy rate of the population was close to fifty percent in 1952. Within this context, Cabral initially avoids overt politics and diligently develops constructive alternatives to the colonial system. One of his last official acts as a state agronomist was to propose sugar beet plantations in Portugal. Given the increasing European demand of sugar, this was a profitable option for the ‘mainland’ to replace the exploitation of sugarcane plantations in its tropical ‘overseas provinces’.

Cabral turned the mirror back to Europe, suggesting a solution to a European agricultural crisis. It was, after all, partially as a consequence of agricultural crisis (as previously addressed from a Eurocentric perspective by Liebig and Marx)35 that European powers had accelerated their colonial projects, a process consolidated with the scramble for Africa at the 1884–1885 Berlin Conference:

‘[e]conomic factors in Europe were one of the causes behind the European settlement of Africa after the Age of the Discoveries. With the simple trade in goods, including enslaved black men, Europeans spent the rewards of the exploitation of the land. But like black Africans, the aim was to produce essential food. Europeans cultivated or forced black Africans to cultivate farm products. […] From the contradictions created, African land is being devastated day after day.[…] In a life that is out of balance, obliged to satisfy not only the new demands created but the requirements of a new social condition, he (the African subject) slowly uproots himself, migrates or is forced to migrate. He abandons the land or doesn’t have the time to assimilate the knowledge that he has created and accumulated over centuries, based on the transmission of empirical knowledge about the environment. […] The lack of balance in the management of Black African soil encourages the emergence of diseases that debilitate the human organism.’36

Later in 1969, already in the midst of the war of independence, in a workshop with the PAIGC political bureau, Cabral discussed different modes of resistance (political, economic, cultural and military). One argument he made for economic resistance was the awareness of the bureaucratic ‘nullity’ of the value of Black African labour through the manipulation of tax, prices and wages: ‘We have analysed the cultivation of peanuts in depth and we have reached the conclusion that it is forced labour.’37 This calculation demonstrated the perpetuation of an exploitative system of labour that continued in Guinea even after slavery was officially abolished38. Cabral works with the tools of Western science in order to diagnose the conditions of the peoples of Guinea-Bissau in relation to soil degradation. In drawing attention to this relation, he anticipated today’s forced migration of African subjects as a result of the historical devastation of the soil.

UNDERGROUND DOUBLE AGENCY

‘I got myself a contract as an agronomist and went to Angola, taking the opportunity to gather comrades to discuss with them the new path we should follow in the struggle for our lands. Under the control of PIDE [International and State Defence Police], comrades.’

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 9.0px ‘Times New Roman’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Amílcar Cabral, ‘Resistência Política’, (‘Political Resistance’), Análise de Alguns Tipos de Resistência, Filipa César, trans, Coleção de Leste a Oeste, 1969–1975, p 26.

Amílcar Cabral

Cabral’s subversive double agency becomes evident when viewing, side by side, his co-current roles as political activist and agronomist between 1948 and 1960. Although serving the Portuguese State could be understood as a submission to the colonial power, the subversive nature of his ‘sub-mission’— a mission under Cabral’s official appointment—is implied. His shift from coded contempt to the overt criticism of the colonial agricultural system manifested in articles such as ‘“’Acerca da Utilização da Terra na África Negra’, which made it difficult for Cabral to operate in Portuguese Guinea.

An early example of this militant subversive approach dates back to 1948, when Cabral had just joined the Casa dos Estudantes do Império or CEI (House of the Students from the Empire, 1944-65) in Lisbon. This academic institution had been created by the Overseas Ministry to promote a sense of global ‘portugality’ among the students from the colonies. Here he communed with Eduardo Mondlane (who became the first president of FRELIMO – Frente de Libertação de Moçambique), Mario Pinto de Andrade (co-founder of MPLA and partner of pioneering filmmaker, Sarah Maldoror), Agostinho Neto (co-founder of MPLA) and many other future anti-colonial leaders. The students quickly subverted the official agenda of this institution, which became a hotspot for young intellectuals to develop a critical discourse about colonial politics and, later, to prepare for armed struggle.

The CEI published numerous short poetry publications and edited a magazine called Mensagem (Message) that focused on non-European Lusophone poetry. Poetry functioned as a ‘cultural’ disguise that allowed these young intellectuals to address the oppression of African and Asian peoples. Technically, the Portuguese political police (PIDE), in the various raids on the CEI and surveillance reports of the students’ cultural activities, had difficulty decoding the poetic musings of an inconspicuous political organisation that was smouldering inside colonial academia39.

After ending the field work in Portuguese Guinea, Cabral continued to work as a state agronomist, now directing his focus to the phytosanitary conditions of food storage40 in Angola, Cape Verde and Lisbon. This research enabled him to move freely between the colonies and the ‘metropole’ and to gain strategic data about Portugal’s economic dependence on overseas products and colonial trade economy, information that he forwarded to the various newly-founded anti-colonial parties in Angola and Mozambique41. In 1955, Cabral founded the MING (National Independence Movement of Guinea) and transferred his agronomic work to Angola, Cape Verde and Lisbon42. Then, in 1956 he co-founded the MPLA (People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola) in Angola, the PAI (African Independence Party, which later became PAIGC) in Guinea, and in Lisbon the MLPCP (Movement for the Liberation of the People of the Portuguese Colonies) and the MAC (Anti-Colonialist Movement)43. This educated elite of the colonised quietly prepared for revolution by subversively using the opportunities provided by the coloniser, turning its tools – agronomy, science, poetry and academic institutions – against its power.

In August of 1959, sailors and merchants demonstrated for better working conditions at the Pidjiquiti port (main port) in Bissau; resulting in a massacre that killed 50 people and left hundreds wounded. This halted all PAIGC attempts at peaceful negotiations to end the colonial Portuguese occupation. Half a year later, in January 1960, Cabral gave up his job as agronomist and went underground, leaving Portugal forever to become a full-time political strategist and theorist of the liberation movement44. The following Spring, in June 1961, hundreds of students from African colonies secretly fled from Portugal to escape the forced recruitment to the colonial military to fight on the other side of the same war. The CEI functioned as the main organisational hub for the escape operation. The date 23 January 1963 marked the start of the armed struggle in Guinea with PAIGC guerrilla militants attacking the Portuguese military base of Tite in the South of the country.

SEMANTICS FOR SOIL RECLAMATION

As mentioned above, Cabral’s first job in Portuguese Guinea was directing the State Farm of Pessubé (Granja de Pessubé) in 1952, which he quickly transformed into an experimental farm45. The agricultural research centre was an attempt to put into practice his vision for the development of Guinea after independence. As Schwarz summarises, Cabral established three main goals for his programme at Pessubé:

‘- the first one was to transform the Farm from a mere unit of vegetable production destined to the colonial political and administrative authorities of the praça [city] and a place for picnics and recreational walks, into a centre of agricultural research – a tool to improve and modernise the production of the farmers;

- the second was to tear down internal walls within which the agricultural services were confined, to approximate them to the farmers, who should be the main beneficiaries;

- the third was that of the interaction of Guinean farmers with those in the neighbouring countries of the sub-region.’

The experimental farm project was intended to change the farming practices, with the aim of emancipating people and repairing the land. The intrinsic operations of the agricultural research institute, rooted in the motto ‘experimentation-dissemination’, already show traces of what later became Cabral’s ‘Theory of Culture’. Cabral developed his revolutionary theory following his emergence from this earlier period of double agency when, under the alias of Abel Djassi, he led the nascent anti-colonial movement while still working as an agronomist for the Portuguese regime. With the launch of the armed struggle he entered the world stage as the leader of PAIGC and a theorist of anti-colonial resistance. His speeches – to the general population, the UN, the guerrilla fighters, guerrilla teachers – are imbued with an ecology of liberation informed by a decolonisation of language itself. As he explained at Syracuse University ‘it is not possible to harmonise the economic and political domination of a people, whatever may be the degree of their social development, with the preservation of their cultural personality.’ He argued that ‘the so called theory of progressive assimilation of native populations’ is nothing but a violent attempt ‘to deny the culture of the people in question’46. For Cabral, the liberation of African people necessitated an act of cultural emancipation at the grassroots level.

The three principles for the experimental farm of Pessubé can be extrapolated to the agricultural programme he devised for a future Guinea: no elitist production of farming products; no walls between the governance at the service of people/farmers, and finally the encouragement –– through Creole and cinema –– of the exchange of agricultural knowledge and interaction among the different ethnic groups in the region47.

Cabral initially trusted that the liberation process would be possible through non-violent protests and the legitimate demand of independence. These strategies were supported by a permanent pedagogical effort towards self-emancipation employing what radical pedagogue Paulo Freire later coined as the coding of language through a situated process of ‘consciencialisation’ (from the Portuguese consciencialização), an active form of consciousness raising as part of an emancipatory political process48. Unfortunately the violent Portuguese repression of Guinean protests, intensified by the tragic massacre at the Pidjigiti port in 1959, made clear that the Portuguese had no intention of emulating other European colonial countries by recognising the right of independence of their former colonies, thus provoking the eruption of the guerrilla war.

In many of his political speeches to guerrillas and peasants in the context of the armed struggle, Cabral insisted in re-naming and re-defining words, geographies and concepts as a decolonising process of ‘consciencialisation’ about systems of power, a semantic operation that enhances the strategic efficiency of warfare. For example: ‘In Guinea, land is cut by arms of the sea that we call rivers, but in depth they are not rivers […] because until we arrive on dry land there is only salty water’49 Guinea’s morphology is a mountainless alluvium, with 70 percent of its soil under sea level. These ‘arms of the sea’ have no word in the colonial lexicon. The awareness of this lack signals something amiss in the colonial epistemology – you only see what you already know. The inadequacy of the Portuguese lexicon is proof of the illegitimacy of their occupation. This tidal condition also suggests the vulnerability of a permeable land inscribed with centuries of invasion. Another example is the tactical and simultaneously semantic concept of ‘centrifugal movement’: ‘[W]e adopted a strategy that we might call centrifugal: we started in the centre and moved towards the periphery of our country50. This came as the big surprise to the Portuguese, who had stationed their troops on the Guinea and Senegal borders on the supposition that we were going to invade our own country.’ This demonstrates how effective tactics result from the coherence and legitimacy of a conscious situatedness by occupied people. Cabral proves the ignorance of the colonial military forces in their miscalculation of where the rebels or terrorists (as the militants of Cabral’s movement were called in New State propaganda) would attack from and with which tactics, and the error of all colonial construction and occupation. The struggle begins in the centre of the land, because it is a people’s struggle, and then moves in a centrifugal manner like a kind of expanded version of the geometric form etymologically embedded in the term ‘revolution’– the revolving turn or course described by celestial bodies.

In 1966, during the first Tricontinental Conference in Havana, Cabral delivered his paper ‘The Weapon of Theory.’ One year later, as part of an agreement with Fidel Castro, Cabral sent young Guineans to Cuba to be trained in medicine, warfare and cinema. Four of them – Sana na N’Hada, Flora Gomes, Josefina Crato, and José Bolama – went to the ICAIC (Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos) to learn filmmaking under the guidance of Santiago Álvarez. But first, they were introduced to the Spanish language and the practice of voluntary work: labour that is not necessarily profitable but teaches an experience of the common and, as Sana N’Hada puts it, a practice for learning ‘humility’51. To be humble is to be next to the humus, to be earthed, to not lose contact with the ground, to stay close to the soil. This voluntary work (and its inherent humility) informed Guinean film production as a grounded cinematic practice at the service of a grassroots revolutionary process. In 1972, the Guinean filmmakers returned from Cuba to begin documenting the on-going war of liberation against Portugal and, after the unilateral declaration of independence, to build the capacity to make moving images in and of an independent nation52.

Still from José Bolama Cobumba, Josefina Crato, Flora Gomes, Sana na N’Hada, Guinea Bissau 6 Years After, 1980 (unfin- ished film), Guinea Bissau, INCA 1979–1980

Still from José Bolama Cobumba, Josefina Crato, Flora Gomes, Sana na N’Hada, Guinea Bissau 6 Years After, 1980 (unfin- ished film), Guinea Bissau, INCA 1979–1980

Cabral never lived to witness the cinema he envisioned, as he was assassinated on 20 January 1973. However, it was two of the Guinean filmmakers whom Cabral had sent to Cuba for training, Sana na N’Hada and Flora Gomes, who produced the cinematic document of the event that Cabral had worked towards, namely Guinea-Bissau’s unilateral declaration of independence on 24 September 1973. In the hills of Boé, the only elevated area of this flat and marshy country, the leaders of the PAIGC gathered their militants for the 1st Popular Assembly53. A bureaucratic ritual in the midst of the jungle declared the Republic of Guinea Bissau independent from Portugal.

In an interview in 2014, Sana na N’Hada explained the cinema programme of the Guinean National Film Institute for the newly liberated country: ‘How would cinema work in an [institutional] way? We had been shooting for about five or six years when we founded the Film Institute. Now, what ought to be done? So we created the “Programme of Rural Promotion by Audiovisual Media”, which meant that, with cinema – along with Creole – we could make people from there understand people from here. We would contribute to imagining a national space.’54 Although some film production took place in Guinea-Bissau after independence, the aspirations to national film production remained unfulfilled. To look at the remains of this militant Guinean cinema today gives us an insight into both their representation of the revolutionary process and the inscription of time, climate and war in the materiality of the now-ruined celluloid. The erosion visible in the remaining celluloid from this militant cinema praxis speaks of an abandonment of revolutionary ambition and care in the postcolony. Neo-colonial erosion is at stake not only in the soil of the nation but also on any surface inscribed by opposition to power.

While national film and television institutions that were set up in Angola and Mozambique after independence actively promoted Standard Portuguese as a national language to promote political unity, in Guinea-Bissau Creole was chosen as a lingua franca between over thirty different ethnic communities. The re-coding of disparate farming practices was entangled with an encoding of language and media, in this case the development of Creole as a new transversal language was harnessed in film as the vehicle of translocal agronomic exchange. Documentaries were planned to be disseminated by mobile cinema units, with the aim of creating a shared knowledge of situated modes of living and farming.

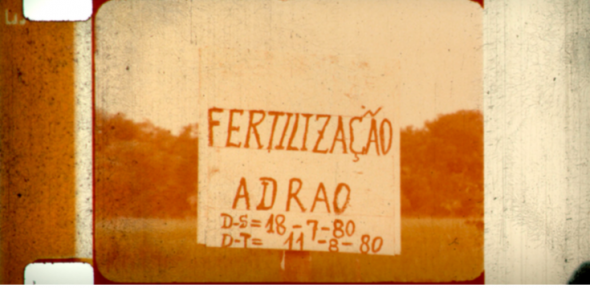

Creole is a language derived from an appropriation of Portuguese vocabulary and the assimilation of oral and ethnic languages (especially from Mandiga syntax), and it was the language Cabral used to communicate with different ethnic groups in the course of the eleven-year-long armed struggle. A particular poetic and advanced aspect of Guinean Creole, also seen in Cabral’s theorisation of revolution, is its metonymic character, for example, ‘pekadur’ is the word for ‘human being’ and means ‘sinner’ – a particular human characteristic becomes the name for the whole. Creole was the understudied inscription of and resistance to 500 years of colonial encounter55. Militant cinema and Creole were the encoding of the struggle into the soil and onto the celluloid emulsion, a deprogramming of the colonial system and epistemological soil reclamation. The ‘composting’ of the celluloid remains –for example of the deeply eroded reels for the never-finished film Guinea-Bissau: 6 Years After from 1979–1980, which depicted various indigenous agriculture practices – can both be seen as the meteorisation of matter analogous to the processes of neo-colonial erosion but also the humus to fertilise a soil literacy needed for future gestures of decolonisation.

In his 1966 Havana speech, Cabral asserted: ‘We note, however, that one form of struggle which we consider to be fundamental has not been explicitly mentioned in this programme […]. We refer here to the struggle against our own weaknesses.’56 One of those weakness was certainly the use of a national model based on a colonial paradigm, that has been born out in the descent into neo-colonialism after independence. My reading of Cabral’s scientific, economic and political writings proposes to understand ‘meteorisation’ as an operational tool in a permanent struggle that is the only possible state of liberation. Cabral was not advocating for a utopian post-colonial oppression-free future from which reparation would follow, but was rather preparing militants, language and soil for a permanent becoming, one that even then could confront the threats to the environment, already anticipating what has been named the ‘capitalocenic’ Earth epoch. The current situation in Guinea-Bissau is one of neoliberal takeover of territory by multi-nationals, upgrading historical extractivist models to new global corporate-colonialist systems, rendering again the complex alluvium ecologies as a contemporary terra nullius, for example, to install Free economic Zones57. ‘Our people are the mountains’ is a counter-extractivist mindset, an animistic activation of the soil, a convocation of various knowledges and a negation of coloniality. A soil reclamation. The inscriptions on and in the palimpsest of the soil tell narratives of both the wretchedness and the liberatory potency of its humus.

Article originally published in Third Text I Filipa César (2018) Meteorisations.

- 1. This text was written in dialogue with Diana McCarty, it profited from Clara López Menéndez reviewing and was enriched by insightful proposals made by editors Ros Gray and Shela Sheikh. It is deeply indebted to conversations with Olivier Marboeuf, Tobias Hering, Suleimane Biai, Stefanie Schulte Strathaus, Aissatu Seide, Flora Gomes, Sana na N’Hada and many other ciné-kins in the context of the project Luta ca caba inda.

- 2. Amílcar Cabral, Our People Are Our Mountains –Amílcar Cabral on the Guinean Revolution, Committee for Freedom in Mozambique, Angola and Guinea, London, 1971, p 11.

- 3. Operating from Conakry – the capital of The Republic of Guinea, the allied southern neighbour, already liberated from French colonialism in 1958 – the PAIGC is laying the ground for a unilateral Declaration of Independence for Guinea Bissau. This momentous event takes place only two years later, in September 1973, although Cabral is not there to witness this victory. He was assassinated in January 1973.

- 4. Amílcar Cabral, Our People Are Our Mountains – Amílcar Cabral on the Guinean Revolution, op cit, p 11–12.

- 5. The UK and Portugal formed an alliance in 1386, which benefitted both Portugal’s determination to hold on to its colonies, and Britain’s attempt to maintain its neocolonial dominance through international institutions such as the Commonwealth. CFMAG was founded on the instructions of Frelimo to pressure the British government to cease its support for the Portuguese colonial war.

- 6. The PAIGC guerrilla forces operating inside the country were mainly formed by elements of the Balanta ethnic group, a society structured horizontally, without kings, chiefs, or hierarchy and therefore no military rankings. See P.A.I.G.C. Unidade e Luta, Publicações Nova Aurora, Lisbon, 1974, p 83.

- 7. ‘Fighting on favorable ground and particularly in the mountains presents many advantages’ Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara in Guerrilla Warfare, New Statesman, London, 1967, pp19–23

- 8. Here I recall the use of the term ‘the multitude’ by Baruch Spinoza, later developed by Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt as a concept of people that have not yet entered a social contract with a sovereign political body, such that individuals still retain the potential capacity for political self-determination. See Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire, London, Penguin, 2005.

- 9. Ecosophy is a term introduced by Félix Guattari to define ‘a multi-philosophy that encompasses social and individual practices with the aim of opening up the possibility of thinking social, mental and environmental matters as interconnected reciprocal ecologies. […] Here we are talking about a reconstruction of social and individual practices which I shall classify under three complementary headings, all of which come under the ethico-aesthetic aegis of an ecosophy: social ecology, mental ecology and environmental ecology’. Félix Guattari, The Three Ecologies, The Athlone Press, London, New Brunswick, New Jersey, 2000, p 41.

- 10. Amílcar Cabral, Estudos Agrários de Amílcar Cabral, Filipa César, trans, Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical, Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisa, Lisbon, Bissau, 1988.

- 11. Before becoming fiction filmmakers known for their debut films Mortu Nega (Gomes, 1988) and Xime (N’Hada, 1994), Flora Gomes and Sana na N’Hada, and their colleagues Josefina Crato and José Cobumba, were educated by the PAIGC to become the pioneers of Guinean cinema. An extensive research on this militant cinema period, 1967–1980, was undertaken recently with the digitalisation of the INCA (Instituto Nacional do Cinema e Audiovisual da Guiné Bissau) archives in 2012. One of the most important films recovered from this process was the historical collective film The Return of Amílcar Cabral (1976). For more information see publications La Lutte N’est Pas Finit, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 2012, Luta ca caba inda: time, place, matter, voice, 1967-2017, Archive Books, Berlin, 2017, The Struggle is not Over Yet – An Archive in Relation, Archive Books, Berlin and CIAJG, Guimarães, 2015 and films Spell Reel (César, 2017), Conakry (César, Kilomba, McCarty, 2013), Mined Soil (César, Marboeuf, 2014) and Cacheu (César, 2012).

- 12. In 1945 Amílcar Cabral received a scholarship to attend the Higher Agronomic Institute at the University of Lisbon. See Iva Cabral, Apontamentos para uma Biografia: Cronobiografia realizada por Iva Cabral, no âmbito do Projecto de Salvaguarda do Património Histórico da África Contemporânea (SPHAC).

- 13. Capitalocene is a term coined by Jason W Moore in Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism, PM Press, Oakland, 2016, p 6.

- 14. Dipesh Chakrabarty, ‘Postcolonial Studies and the Challenge of Climate Change’, New Literary History, vol 43, no 1, Winter 2012, p 13; and Dipesh Chakrabarty, ‘The Climate of History: Four Theses’, Critical Inquiry, vol 35, no 2, Winter 2009, pp 197–222.

- 15. Amílcar Cabral, Estudos Agrários de Amílcar Cabral, op cit, p 63.

- 16. See Patrick Chabal, Amilcar Cabral: Revolutionary Leadership And People’s War, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1983; António Tomás, O fazedor de utopias: uma biografia de Amílcar Cabral, Tinta-da-China, Lisbon, 2007 and Julião Soares Sousa, Amílcar Cabral (1924-1973): vida e morte de um revolucionário africano, Vega, Lisbon, 2011.

- 17. Amílcar Cabral, Revolution in Guinea – An African Peoples Struggle, Stage 1, London, 1969, pp 73–90. In an anecdotal twist of history, this Portuguese Cuba, according to local mythology, is the birthplace of Christopher Columbus, who then named an island in the Caribbean after it: Cuba, where Cabral would later deliver his important speech ‘The Weapon of Theory’ at the First Tricontinental Conference in 1966.

- 18. José Neves, Ideology, Science, and People in Amílcar Cabral História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro 2017, p 8.‘This is apparent in his bachelor thesis, a study that bore witness to a shift in the field of pedology, when the latter discipline took on ecological concerns, in the sense of concern not only for land, flora, and fauna but also for men and their social relations.’ http://www.scielo.br/pdf/hcsm/v24n2/en_0104-5970-hcsm-S0104-597020170050... , accessed 22 January 2018.

- 19. As Achille Mbembe writes, ‘The notion “postcolony” identifies specifically a given historical trajectory – that of societies recently emerging from the experience of colonisation and the violence which the colonial relationship involves.’ Achille Mbembe, On the Postcolony, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2001, p 102.

- 20. In Cosmologies – Perspectivism, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro writes about the prosopomorphic agency – from the Greek prosopopoeia,‘the putting of speeches into the mouths of others’ or ‘an imaginary or absent person is made to speak or act’.

- 21. Karl Marx, Das Kapital, Kritik der politische Oekonomie, erster Band, Verlag von Otto Meissner, Hamburg, 1867.

- 22. Vilém Flusser, ‘The Gesture of Planting’, Gestures, Nancy Ann Roth, trans, University of Minnesota Press, 2014, p 101.

- 23. For more information on the ‘New State’ Portuguese Government, see: Patricia Vieira, Portuguese Film, 1930-1960: The Staging of the New State Regime, Bloomsbury, New York and London, 2013 and on the Portuguese political State Police PIDE (Polícia Internacional de Defesa do Estado), Irene Flunser Pimentel, A História da PIDE, Círculo de Leitores, Temas e Debates, Lisbon, 2007.

- 24. New State Portugal (1933–74) suffered a decades-long agricultural crisis that followed the world depression of 1929. In the fifties, when Amílcar Cabral made his studies on Alentejo’s soil, industrialisation of agriculture was almost non-existent and the poor rural areas of Portugal suffered an exodus to the colonies and other countries, particularly France.

- 25. Amílcar Cabral, Estudos Agrários de Amílcar Cabral, op cit, pp 120-121.

- 26. John Bellamy Foster, ‘Marx´s Theory of Metabolic Rift: Classical Foundations for Environmental Sociology’, American Journal of Sociology, vol 105, no 2, The University of Chicago Press, 1999, p 376.

- 27. This is an appropriation of Donna Haraway’s concept of ‘situated knowledge’ as developed in ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’ in Feminist Studies, vol 14, no 3 Autumn, 1988, pp 575–599. Haraway introduced this concept in the context of a feminist critique of hegemonic modes of historical knowledge production. Situated knowledge is a knowledge produced by and producing a specific subjectivity. It is a call to give the right of speech to those historically kept silenced, the workers, the women, the oppressed, the enslaved and nature.

- 28. It is worth mentioning that the African colonies were defined by the New State as ‘overseas provinces’ – i.e,, part of Portugal rather than separate colonies, and the claim was that the assimilated elite of Africans (actually a minute proportion of the colonised population) were Portuguese, by virtue of economic status, education and renouncing their African languages and culture.

- 29. As Schwarz states: ‘The FAO agricultural census project approved by the Portuguese government in 1947 and soon put in the drawer where it slept for more than four years, is quickly retaken by Cabral, few months after his arrival at Pessubé, which he studies, plans and executes. For him, the census was not only a set of tables and numbers, but also the possibility to read, comprehend and act on the prevailing agricultural dynamic’. Carlos Schwarz, An Agronomist Before His Time, Nov. 2012, http://www.adbissau.org/pensar-amilcar-cabral, accessed on 5 May 2016

- 30. Amílcar Cabral, ‘In Defence of the Earth I–IV’, op cit, pp 63–79

- 31. Amílcar Cabral, ‘On the Use of the Earth in Black Africa’, Estudos Agrários de Amílcar Cabral, op cit, pp 241–249.

- 32. ‘Économie de traite’, trade economy meant all economic relationships associated with the marketing of agricultural products that African farmers offered for sale for the purpose of exploitation.

- 33. ‘Mesology’ in the fifties was used in scientific jargon for what is called ‘ecology’ today. Amílcar Cabral, Estudos Agrários de Amílcar Cabral, op cit, p 248.

- 34. Justus von Liebig in his Letters on Modern Agriculture (1859), as cited by John Bellamy Foster in Marx’s Ecology – Materialism and Nature, Monthly Review Press, New York, 2000, p 153.

- 35. For further considerations on a contemporary critique of Karl Marx’s Eurocentrism, see Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Towards a History of the Vanishing Present, Harvard UP, Boston, 1999. In an ambitious attempt to complicate the Eurocentric narrative of globalised capital, Spivak moves to consider the rhetorical and geopolitical blind-spots in Marx’s definition of capitalist modes of production. As Spivak suggests, the conditions for radically disempowered social groups in capitalist production present a crisis in the cognitive abilities of Western critical theory and cultural politics.

- 36. Amílcar Cabral, Estudos Agrários de Amílcar Cabral, op cit, p 248.

- 37. Amílcar , ‘Resistência Económica’, (‘Economic Resistance’), Análise de Alguns Tipos de Resistência, Filipa César, trans, Coleção de Leste a Oeste, 1969/1975, pp 35–36.

- 38. Cabral’s critique of the exploitation of Black Africans and their land chimes with Denise Ferreira da Silva’s recent elaboration on the negative value culturally imposed on Blackness throughout the West’s historical narrative of transparency. Da Silva proposes to recalculate Marx’s Theory of Value to acknowledge that, ‘in the modern Western imagination, blackness has no value; it is nothing’. This move, substituting Blackness’s negativity (-1) with nullity (0) as its operational value, not only denounces the racialised aspect of the Capitalist system by highlighting its bias towards Black subjects, but also disrupts any attempt at calculating the value of Blackness. Denise Ferreira da Silva, ‘1(life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = & - & or &: On Matter Beyond the Equation of Value’, e-flux Journal, no 49, February 2017, pp 9–10.

- 39. For more information read Patricia Leal, ‘The House of the Students of the Empire. An Unexpected Antechamber of the African Liberation Movements’ in The Struggle is Not Over Yet – An Archive in Relation, op cit, pp 87–114 and Manuela Ribeiro Sanches, ‘(Black) cosmopolitanism, transnational consciousness and dreams of liberation’, Red Africa: Affective Communities and the Cold War, Black Dog Publishing, London, 2016, pp 68–79.

- 40. Amílcar Cabral, Estudos Agrários de Amílcar Cabral, ‘Condições Fitossanitárias de Produtos Ultramarinos em Armazéns do Porto de Lisboa’ (‘The Phytosanitary Conditions of Overseas Products Stored in Warehouses at the Port of Lisbon’) pp 703–778.

- 41. From 1957 onwards, Cabral intensified his operations in both fields and it is clear to see how not only strategically, but also in terms of content, both agencies were interwoven: in 1957 he had a meeting in Paris, where he consulted and studied the development of the struggle against Portuguese colonialism; in 1958 he attended the 1st Conference of African Peoples in Accra as an observer and the XXIV Luso-Spanish Congress on the progress of Sciences in Madrid. In December he chaired an enlarged meeting of the PAI, in Bissau, where he decided on the reorganisation of the party and drew up an action plan with the priority to mobilise the people in the countryside. In 1959, during a brief stay in Bissau, he presided over a meeting for the merging of other anti-colonialist movements with the PAI, that resulted in a single unified party – the PAIGC. And in Dakar he founded the Liberation Movement of Guinea and Cape Verde (MLGCV), with connections to the PAIGC.

- 42. Amílcar Cabral, Estudos Agrários de Amílcar Cabral ‘O Problema do Estudo Macro e Microclimático dos Ambientes Relacionados com os Produtos Armazenados’, 1956, pp 269–273; ‘O Estudo do Microclima de um Armazém em Malanje (Angola)’,1956, pp 275–290; ‘Sobre a Acuidade do Problema do Armazenamento no Arquipélago de Cabo Verde’ (Conferência Internacional dos Africanistas Ocidentais), 1956, pp 445–513.

- 43. It could be said that the young Cabral and his peers were involved in a kind of subversive and surreptitious use of the academic institution that prefigures the methodology later articulated by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney as the ‘Undercommons’, a practice that undermines the neoliberal academic edifice through clandestine activities that exceed the limitations and desires imposed by the capitalist agenda: ‘The university needs what she bears but cannot bear what she brings. And on top of all that, she disappears. She disappears into the underground, the downlow lowdown maroon community of the university, into the undercommons of enlightenment, where the work gets done, where the work gets subverted, where the revolution is still black, still strong.’ Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study, Minor Compositions, Wivenhoe, New York, Port Watson, 2013, p 26

- 44. Cabral’s former colleague, the Portuguese agronomist Ário Lobo de Azevedo, stated ‘At the end of 1959, I mean, I can’t say precisely the exact date, I was discussing a new task with Amílcar Cabral in Angola. Amilcar had difficulties in committing himself. That was when he informed me that he was going to move away from the team; for many reasons, his life was about to change direction. (…) Was Amilcar Cabral fully aware of his option while abandoning the group of agronomists he was collaborating with? I believe he was. As far as I’m concerned, remembering that day, I would say that the world of agronomy and I became a bit poorer but the world definitely richer’ in ‘A propósito de dimensão humana de Amílcar Cabral’, Estudos Agrários de Amílcar Cabral, op cit, p 13

- 45. Amílcar Cabral, Estudos Agrários de Amílcar Cabral, op cit, pp 181–206.

- 46. Amílcar Cabral, National Liberation and Culture (this text was originally delivered on 20 February 1970 as part of The Eduardo Mondlane Memorial Lecture Series at Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, under the auspices of The Programme of Eastern African Studies. Maureen Webster, trans) http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/cabralnlac.html, accessed on twenty-second January 2018.

- 47. Carlos Schwarz, An Agronomist Before his Time, op cit.

- 48. In 1975, Paulo Freire is invited by Commissioner of Education Mário Cabral to work with the post-revolutionary government of Guinea Bissau on the development of a pedagogical system for the newly liberated nation. Freire develops the concept of political literacy that includes a specific concept of language literacy that is never detached from a process of consciencialisation of pupils’ own life conditions and practices of solidarity, and underlines the dynamic aspect of his pedagogical concept as being developed in and for the specific context. See Paulo Freire, ‘Introduction’ and ‘Coding and Generative Words’, Pedagogy in Process: Letters to Guinea Bissau,, Bloomsbury, London and New York, 1978/2006, pp 2, 81.

- 49. P.A.I.G.C. Unidade e Luta, Filipa César, trans, Publicações Nova Aurora, Lisbon, 1974, p 108.

- 50. Amílcar Cabral, Revolution in Guinea – An African Peoples Struggle, op cit, p 10.

- 51. Sana na N’Hada in Spell Reel (César, 2017).

- 52. Regarding the birth of Guinean cinema as part of the decolonising vision of Cabral, see Filipa César’s collaborative project with Sana na N’Hada, Flora Gomes, and others, Luta ca caba inda (The struggle is not over yet). Luta ca caba inda starts as a project of digitalisation of the remains of militant Guinean cinema and takes the form of discursive screenings, mobile cinemas, encounters and discussions, writings, walks, film productions and publications. See Luta ca caba inda: Time Place Matter Voice, 1967–2017, Berlin, Archive Books, 2017.

- 53. On 24 September 1973, the PAIGC declares its unilateral independence in the bushes of Boé. Within less than a month eighty countries around the world had recognised the independence of Guinea Bissau, despite the ongoing armed conflict with colonial Portugal. Only the Carnation Revolution in Portugal in April 1974 finally ends Portuguese occupation in Guinea.

- 54. Sana na N’Hada in Spell Reel (César, 2017)

- 55. For more information on Guinean Creole please see Teresa Montenegro, Kriol Ten : Termos e Expressões, Ku Si Mon Editora, Bissau, 2002/2007 and Alain Kihm, Kriyol Syntax – The Portuguese based Creole Language of Guinea-Bissau, John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, 1994.

- 56. Amílcar Cabral, The Weapon of Theory, address delivered to the first Tricontinental Conference of the Peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America held in Havana in January, 1966.

- 57. https://www.zonafrancabolama.com/en/ accessed 1 May 2018